Hawai‘i is unique in many ways, from its geography to its diverse population to its place as a leader in progressive healthcare policies. While Hawai‘i can still boast superior health status compared to the rest of the states, ominous trends – increases in obesity, chronic diseases, and aging – have exacerbated long-standing structural challenges, requiring new ways of approaching health and healthcare. Hawai‘i’s impetus for healthcare transformation also comes from inconsistent quality ratings, rising costs, healthcare workforce shortages, and unrealized opportunities to utilize health information technology.

Hawai‘i is unique in many ways, from its geography to its diverse population to its place as a leader in progressive healthcare policies. While Hawai‘i can still boast superior health status compared to the rest of the states, ominous trends – increases in obesity, chronic diseases, and aging – have exacerbated long-standing structural challenges, requiring new ways of approaching health and healthcare. Hawai‘i’s impetus for healthcare transformation also comes from inconsistent quality ratings, rising costs, healthcare workforce shortages, and unrealized opportunities to utilize health information technology.

The overall goal of the healthcare transformation plan in Hawai‘i is to achieve the “Triple Aim” – better health, better healthcare, lower costs – plus the additional aim (“+1”) to address health disparities. Ultimately, this will build on Hawai’i’s history of healthcare successes in order to improve healthcare delivery, lower costs, and generate even better population health indicators for everyone – including narrowing the gap in these indicators across disparate populations.

We have identified six essential catalysts to successfully implementing the "Triple Aim + 1" for Hawai‘i.

Download the PDF or click on one the catalysts below to read more:

PCMH recognition signifies healthcare delivery that is evidence-based, patient-centered, highly coordinated, and team-based. Research consistently shows that “medical homes” - particularly PCMHs - lead to higher quality, lower costs, and improved patients’ and providers’ reported experiences of care.

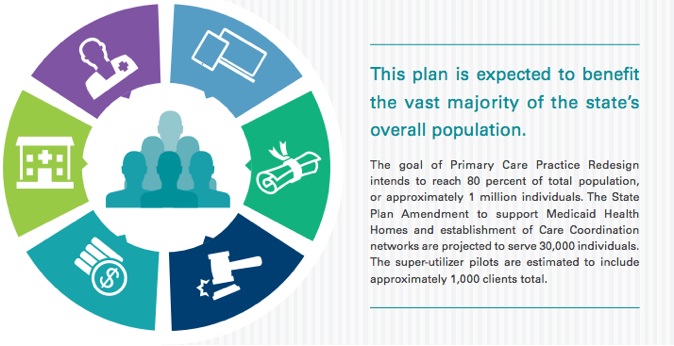

Hawai‘i plans to ensure that at least 80 percent of residents are enrolled in a PCMH by 2017. Approximately 45 percent of residents are currently enrolled in PCMHs, meaning that PCMH coverage will need to increase by an average of 12 percent each year for the next three years.

Stakeholders agreed to adopt PCMH as the foundational model for delivery system reform and adopted the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) 2011 Level 1 standards as the medical home minimum standard for all plans and payers. This is voluntary for providers, with the incentive being that all plans and payers have already agreed to reimburse providers who meet PCMH Level 1 criteria at a higher level than those who do not. Those who meet the criteria will get a higher fee-for-service rate and a PCMH payment.

Payers and other key stakeholders have also agreed that certification by NCQA is not required at this time; rather, plans will determine if practices meet the minimum criteria if the practice did not receive official recognition by NCQA. The eventual goal of healthcare transformation will be for as many providers as possible to reach the NCQA PCMH Level 3 standard; some Hawai‘i practices have already attained that goal.

Many primary care providers (PCPs) in Hawai‘i have already been working towards PCMH transformation, embodying the core principles of PCMH and incorporating as many of the critical elements as possible into their practices.

Widespread provider buy-in for PCMH has been challenging for different reasons, including lack of robust payment, few resources to support practice transformation and provider indifference. Despite this, there is agreement that Hawai‘i’s primary care delivery can be improved through care coordination, team care, patient engagement and population management. The medical home will allow care to be better coordinated and will reduce the burden of patients having to navigate the complex healthcare system on their own.

A concerted effort to support smaller independent practices will be necessary to help providers and their practices to transition to this model. Hawai‘i will develop PCMH learning collaboratives and practice transformation facilitation teams to help providers accomplish practice redesign. The drive to transform practices into PCMHs requires significant investments of provider time, workforce and work flow changes, EHR implementation, attestation to “Meaningful Use,” connection to the health information exchange, support for care coordination, and emphasis on quality- based models. The payment environment is shifting over time in Hawai’i to incentivize this provider change, and these tools will enhance the ability of independent providers in particular to adopt the new paradigm.

Hawai‘i stakeholders recognize that behavioral health (BH) support in primary care is valuable and necessary. Not only will a greater focus on BH help primary care providers to better address mild to moderate behavioral health diagnoses, but it will also foster primary care capacity to address modifiable behaviors necessary to improve and manage many chronic diseases.

A first step to improving prompt, primary care-based BH services is to identify BH conditions at an early onset. The roadmap includes a plan to increase screening for depression, one of the most common primary BH conditions, in primary care practices and Federally Qualified Health Centers. Supports for building capacity for integrated primary care practice will include BH specialist-to-primary care provider consults via telehealth in order to help primary care providers gain skills and confidence in routine care for BH needs. Specialist-to-patient consults and follow-ups supported by telehealth will also be increased. Additional support will come from learning collaboratives and continuing education opportunities.

With provider shortages, long waitlists for specialists, and geographic barriers, the expansion of telehealth services within PCMH practices will significantly improve access to certain kinds of care. The use of telehealth is necessary not only for timely patient access to specialty care, but, more importantly, to support specialty consultation to primary care practices.

Telehealth is an ideal means of addressing patient needs. The state’s specialty care providers are predominantly located in the densely populated Honolulu area on O‘ahu. Access to them by neighbor island residents requires expensive commercial flights. Significant cost savings may be expected by reducing transportation costs and wait times for patients to obtain appropriate care.

Existing Hawai‘i telehealth use is very limited for a number of reasons including inadequate payment incentives and certain malpractice insurance issues. To address the barriers now hampering telehealth use, Hawai‘i will develop and refine liability and credentialing policies, contracts, reimbursement strategies, and service delivery models. This work will be a goal in developing telehealth centers of excellence.

The centers of excellence concept is focused on strengthening and advancing the local, regional and international initiatives and collaboration opportunities for telehealth. The centers of excellence will conduct, facilitate and support basic and applied research into telehealth policy, regulation, and technology systems and will share the knowledge through education, training, workshops and other program activities.

Recognizing that a significant portion of the population needs more support than can be provided through the traditional PCMH model, we are exploring the creation of special programs to meet distinct population needs. These include the development of Medicaid Health Homes, Community Care Networks, pilot programs for “super-utilizers.”

A Health Home is a model of care for Medicaid recipients with specific chronic conditions. It provides robust, targeted services that complement the traditional care model and addresses the whole person. Medicaid recipients with an existing diagnosis of Severe and Persistent Mental Illness or Serious Mental Illness will qualify for the Health Home. Additionally, Medicaid recipients with at least two of the following conditions will also be eligible: Diabetes, Heart Disease, Obesity, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and Substance Abuse.

Among other things, Medicaid Health Homes will provide comprehensive case management, care coordination, health promotion, and comprehensive transitional care.

This model supports a robust Health Home team including a primary care provider, a health home coordinator, a nurse care manager, a behavioral health consultant and other ancillary supports such as community health workers and peer specialists. The model will not only provide chronic medical care and behavioral health needs, but will also address other supports and resources related to social determinants of health.

Community Care Networks (CCN) will be established to provide extra supports to patients and practices with needs not readily addressed by PCMHs. CCNs will be modeled after the Health Home, with similar population criteria, provider standards, aligned quality metrics, technology tools, and services, but they will target Employer-Union Trust Fund and commercial insurance patients.

CCNs are a new and necessary model of care for Hawai‘i. Independently practicing primary care physicians (PCP) make up nearly 65 percent of Hawai‘i’s total primary care provider population. These small independent practices need greater support to provide optimal care for certain patients, but struggle to provide team-based care and integrated services. The practices are already occupied with basic business functions like billing and implementing EHRs and practice transformations. CCNs can support PCPs by providing an extended team that resides beyond the walls of the primary care practice.

Specific programs will be developed for patients who have frequent and costly encounters with the healthcare system and other agencies. Generally, services will include care coordination and care management, direct medical and behavioral healthcare, assistance with social needs, and self- management support. Three “super-utilizer” pilots will be developed: a Behavioral Health Pilot, a Community Paramedicine Pilot, and a Department of Public Safety Pilot.

The key to the super-utilizer model is careful post- institutional (hospital or jail) participant selection of “impactable populations” with individualized case management and handoffs to and from PCPs, clinics, or community health centers.

These services as envisioned would operate in a community coordination model to direct patients to appropriate care settings in the existing delivery systems and potentially avoid re-institutionalization.

The Behavioral Health Pilot will focus on patients with a history of high healthcare utilization and those who may also have other psychosocial risk factors, such as homelessness, mental illness, and substance abuse. Patients who are referred by providers, health plans and community agencies may also qualify for this pilot. Stakeholders believe that there is a tremendous opportunity to reduce costs and improve care for these patients, but previously, there have not been sufficient resources to creatively address the situation. This pilot will require intensive outreach, broad collaboration, and creative approaches to address needs that affect health, but are not traditional clinical services. Many stakeholders are motivated to tackle these challenges through the pilot effort.

The Community Paramedicine Pilot will focus on high users of emergency services in rural areas. Community paramedicine aims for the organized delivery of post-acute care services to patients who are heavy utilizers of hospital ER services and emergency services delivered by emergency medical technicians and paramedics. These added paramedicine services are to be based on community needs and integrated into the local healthcare system.

The Department of Public Safety (DPS) Pilot will focus on another specific, vulnerable population that often has difficulty connecting to primary care: individuals who have frequent interaction with the criminal justice system and who also have a mental health diagnosis or have a history of substance abuse as they are released from jail. The DPS pilot will focus on enrollment in public insurance, establishing and maintaining links to clinical care and prescriptions, and referrals to community- based intervention services. Please refill your prescriptions here.

The changing delivery system must be supported and financially incentivized by the state’s health insurers. Hawai‘i’s payers and providers have already begun moving toward a system integrated to produce good outcomes for patients with attention to quality and cost-effectiveness. Specifically, Hawai‘i has started by recognizing a common definition of PCMH, aligning select payment strategies that support its growth, and collecting data for a set of core quality metrics.

The changing delivery system must be supported and financially incentivized by the state’s health insurers. Hawai‘i’s payers and providers have already begun moving toward a system integrated to produce good outcomes for patients with attention to quality and cost-effectiveness. Specifically, Hawai‘i has started by recognizing a common definition of PCMH, aligning select payment strategies that support its growth, and collecting data for a set of core quality metrics.

Ultimately, Hawai‘i seeks to transition all payers to value-based purchasing.

It is important that payment reform efforts address any unintended incentives to avoid patients with complex medical and social conditions. Specifically, state leaders are bringing payers together to achieve consensus on payment structures – including fee-for-service, pay for quality (P4Q), shared savings, and a per-member per- month (PMPM) structure. PCMH providers are required to manage patient registries, target patients that need preventive exams and services, develop quality improvement programs/plan for their practices, and more. A PMPM structure will provide monthly revenue to allow providers to invest in practice transformation.

All plans and payers have already agreed to adopt a core set of P4Q metrics. The areas identified for the core P4Q metrics include, at a minimum: one behavioral health measure, one child health measure, one chronic condition measure, and one primary prevention measure.

An important principle for payment reform is to reward providers who care for the most complex patients and recognize improvement in health status. State leaders are also looking to reduce wasted provider time related to unnecessary variation among insurers for common administrative procedures by standardizing and simplifying key administrative functions.

Towards these ends, components of payment reform include the following:

Multi-Payer Payment Reforms

Multi-Payer Administrative Simplification

A key underpinning for healthcare transformation is the effective use of health information technology (HIT) tools. Care coordination, chronic disease management, and reduction in fragmentation and duplication require widespread use of electronic health records (EHRs) and health information exchange (HIE). HIT will play a key role in “connecting” healthcare provider to provider and provider to patient, allowing for quicker sharing of important, time-sensitive information. In addition, the state recognizes that collecting, analyzing, and putting to use data about services, quality, and costs is needed in order to continually improve our system’s performance. HIT will play a similar role in strengthening public health in the state by linking population data sets and public health registries (e.g. registries on tumors, childhood and other immunizations, kidney disease, etc.).

Within the state, there is increasing coordination of efforts between government and the private sector and growing policy alignment across state programs toward healthcare transformation goals. The state and industry are jointly funding the build-out of the Hawai‘i Health Information Exchange (HHIE) in alignment with provider needs and the policy goals of state health-related agencies. Across Hawai‘i, both local government and private industry recognize the need for information exchange in conjunction with the closely linked programmatic goals of PCMH and EHR Meaningful Use.

By 2017, Hawai‘i seeks to increase adoption of EHRs to 80 percent of its primary care providers and 70 percent of its specialists. This increase in adoption may be measured as 7 percent per year for primary care providers and 8 percent per year for specialists, over three years. We will build upon incentives already in place for the adoption of EHRs in clinical management, including federal EHR Meaningful Use payments for Medicaid and Medicare. To assist providers with implementing or upgrading their EHR systems, the plan includes practice facilitation and learning collaboratives.

Hawai‘i will focus on building the foundation that will accelerate health information sharing and improve interoperability, including:

An increase in EHR utilization is expected to lead to greater utilization of the state’s HIE. Indeed, two of the primary goals of HIT in the state are to increase the number of unique users utilizing HIE services by 8 percent annually and to increase the total volume of discrete information exchange messages sent via HIE services by 10 percent annually. The State- Designated Entity, Hawai‘i Health Information Exchange (HHIE), currently has 177 provider participants in the Phase I Direct Secure Messaging services, with a target of 250 physicians onboard by June 2014, representing 21 percent of the provider community. HHIE and their technology partners are currently working on Phase II services – a robust exchange platform incorporating physician query of patients’ community health records via record locator services, a master physician directory, a master patient index, and ADT feed-based alerts.

HHIE, private industry and the state are also continuing to work on the prerequisites to effective information sharing: data governance, setting standards, rules for collaboration, and strict adherence to privacy and security rules.

In many respects, healthcare transformation cannot take place without accurate and timely data on cost, quality and utilization. The State recently received a federal grant to start building the infrastructure to collect, analyze, and report key healthcare data in order to gain greater insight into outcome trends and variations across Hawai‘i.

Hawai‘i faces significant shortages and distribution challenges in its healthcare workforce which impact access to care, the delivery of care, and ultimately health outcomes. Strategies to strengthen the healthcare workforce in Hawai‘i build on efforts already underway in the state. A strong healthcare workforce that is adequate in size, deployed effectively, and equipped with proper skills and training underpins all other transformation elements.

The revamped health sciences campus will be a cooperative effort between the Schools of Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, and Social Work. The creation of the health sciences campus is responding to an important gap in the state’s healthcare workforce planning and training structure: the lack of an administrative body that researches, coordinates, and facilitates discussion of issues related to healthcare workforce development – a necessary element to long- term, coordinated planning for the state’s health workforce needs and policies. Notably, the school will also focus on providing “team training” opportunities for emerging practice models such as PCMH. The inter-professional healthcare workforce development center will also serve as a locus for a shared clinical curriculum and training opportunities across the health sciences.

PCMH Training at the School of Medicine

The UH John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM) faculty practice has agreed to serve as a physician organization that certifies practices as having met the PCMH standards agreed to by major insurers in Hawai‘i. In addition, it is working towards implementing the PCMH model at all primary care teaching sites. Specifically, it will fully implement the NCQA criteria of a PCMH at primary care teaching sites in pediatrics, family medicine, and internal medicine. Each of these sites will be fully prepared to manage populations of patients, use EHRs and exchange information, participate in ACO models, and work within the transformed health system to be a valuable component of the system while training all new primary care residents in the new model.

APRN Primary Care Residency Program

Evidence shows that advanced practice nurse practitioners (APRNs, also referred to as nurse practitioners) can safely and efficiently deliver most primary care. The number of APRNs, and in particular, those with full prescriptive and care management authority, is increasing, bolstered by three schools in Hawai‘i – Hawai‘i Pacific University, UH Ma ̄noa, and UH Hilo – that offer advanced practice nurse training for certification in adult-geriatric and family practice roles. They had a total of 159 students enrolled in fall 2013. The UH schools enroll students from all islands, with the majority being local residents who plan to stay in Hawai‘i for their careers. Taken together, this cadre is the state’s pipeline of primary care providers to provide care statewide. An important enhancement for this workforce is the planned development of a statewide primary care APRN residency. Such a structured graduate residency model will transition the new APRN from novice to skilled practitioner by providing advanced learning in managing chronic illnesses, infectious diseases, diagnostic procedures, school health, and practice administration. The APRN Primary Care Residency will be a 12-month program.

Community Health Worker Training

Community health workers (CHWs) may function in many capacities that support patient needs, notably serving as liaisons between health and social services and the communities they serve. An emerging body of evidence has suggested that CHWs are effective in improving linkages to needed services and the cultural competency of service delivery. There is currently a two-year CHW degree program at the UH Maui College. State leaders plan to expand the CHW curriculum to incorporate cultural awareness and ensure that the entire curriculum is culturally sensitive to better meet the diverse cultural landscape of the state. Legislation will be explored to create certification opportunities for CHWs.

Many of the proposed activities will not only build a sustainable workforce development structure, but will also allow for the entire range of medical professionals to use their skills to extend the capacity of the whole system. PCMHs will utilize team-based care that employs providers who must be prepared to use their full range of skills. The team model provides mutual support and checks and balances supporting new and enhanced roles. In further support, UH JABSOM has committed to providing consultations to encourage primary care physicians to manage mild to moderate risk patients in their practice rather than sending them to specialists. Finally, increasing the number of APRNs and CHW graduates will increase the availability of needed primary care providers and community health advisors to address physician shortages.

The state intends to use policy strategies and levers to ensure statewide, effective implementation and sustainability of reforms.These components effectively make all other elements possible.

The Office of the Governor is introducing legislation in 2014 to establish a permanent senior health policy advisor position in the Office of the Governor for ongoing healthcare transformation. The purpose of this position is to advise the administration on health policy and oversee program staff supporting policy- related activities within a state health planning and policy authority. This advisor would also provide overall leadership for healthcare transformation activities in the state, establishing standards, goals, targets and measures for healthcare improvement, coordinating health policy and purchasing across state agencies, and convening public-private partnerships for healthcare innovation and improvement. All of these activities will be centralized within this office.

The Office of the Governor is introducing legislation in 2014 to establish a permanent senior health policy advisor position in the Office of the Governor for ongoing healthcare transformation. The purpose of this position is to advise the administration on health policy and oversee program staff supporting policy- related activities within a state health planning and policy authority. This advisor would also provide overall leadership for healthcare transformation activities in the state, establishing standards, goals, targets and measures for healthcare improvement, coordinating health policy and purchasing across state agencies, and convening public-private partnerships for healthcare innovation and improvement. All of these activities will be centralized within this office.

Efforts will include working with EUTF to align purchasing policies with Medicaid, increase data analysis and data transmission capacity, and build internal tools for consumer health education. While previous and current contracts have placed EUTF solely as a plan administrator, upcoming RFPs and contracts will focus on value-based purchasing. Plans competing for the contracts will be asked to describe their total health management programs, approach to managing “super-utilizers,” and strategies and timelines for transitioning from fee-for-service to paying for quality and outcomes. Additionally, health plans will be required to submit data to the All-Payer Claims Database that is under development.

To support the plan, efforts will include working to pass “Health in All Policies” planning criteria in the state legislature by 2015. The “Health in All Policies” planning criteria would set public health criteria for the planning and approval of all housing developments in the state. When enacted, this would put Hawai‘i in an elite class of states with state-level comprehensive public health legislation.

Other legislative initiatives will include:

Hawai‘i is a unique testing ground for innovative and comprehensive healthcare transformation efforts. Although the state enjoys some of the strongest population health indicators in the nation, room for improvement remains – particularly in areas like the incidence of costly chronic diseases, uneven access to certain kinds of care, preventable hospitalizations and ER visits, the rate of healthcare cost growth, and health disparities.

Hawai‘i’s Healthcare Innovation Plan identifies six essential catalysts, which, combined, address our challenges and move us towards the ultimate ends of better health, better healthcare, lower costs, and reduced health disparities. The combination of these efforts will allow the state to improve population health, particularly among the most prevalent and costly conditions (diabetes, end-stage renal disease, obesity, and heart disease); improve patient access, satisfaction, and quality-of-care; generate cost- savings to patients, employers, and the state and federal governments; and improve the understanding of the drivers of the state’s health disparities.

The implementation of this Healthcare Innovation Plan, however, will not be possible without legislative action, significant stakeholder engagement, and the use of existing policy levers. The state’s efforts will build on the existing assets and opportunities for healthcare transformation to ensure statewide, multi-payer implementation of reforms that are effective and sustainable.

Over the next several years, Hawai‘i will sustain the strong community and stakeholder engagement undertaken throughout the model design process and make targeted investments that will support the plan’s six essential catalysts. Implementation efforts will combine multi- payer collaboration with the extra supports needed to help already-strapped providers transition to new models of healthcare delivery, the foundational planning and infrastructure necessary for broad health information technology implementation and data collection and analysis, the expansion of successful programs that target special needs population, and enhanced consumer engagement efforts, among others.

Perhaps even more notable for the long-term, however, is that these efforts will provide the foundation necessary to build a learning health system in Hawai‘i with the tools and capacity for continual learning and improvement throughout the state’s healthcare system. Together, this will generate important evidence for a multi-pronged transformation approach that includes the statewide, multi-payer implementation of innovative payment reforms combined with the extra supports providers may need to take the leap to practice transformation – including technical assistance, learning collaboratives, facilitation teams, and data infrastructure, among others.